Virtual Currencies — Coins of the Wild West?

Source: Wall Street Journal

Published: May 17, 2017

Today’s featured article is a subscription-only analysis from the Wall Street Journal. Initial coin offerings are the proverbial next big thing in the world of cryptocurrencies. But are they an investment?

How a Bitcoin Clone Helped a Company Raise $12 Million in 12 Minutes

When tech startup Gnosis raised about $12.5 million in April, the company didn’t tap the typical Silicon Valley funding network of venture-capital firms or wealthy investors. Instead, it auctioned tokens online in a process called an “initial coin offering.” They sold out in 12 minutes.

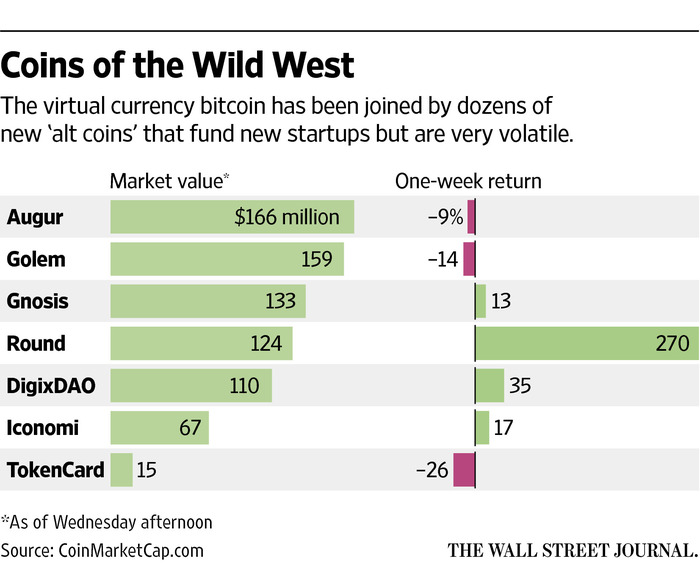

These digital coins are essentially clones of the virtual currency bitcoin, which has come under scrutiny for its use in last week’s global hacking attack. The newer coins are the proverbial next big thing in the world of cryptocurrencies, but also pose big risks to buyers.

The digital coins theoretically can be used to one day purchase services from issuers such as Gnosis, which is building a prediction market for things like companies’ quarterly earnings and the price artwork will fetch at auction.

Most new coins, though, aren’t equity in the companies issuing them; they often don’t confer ownership rights. Nor do they give holders a claim or interest in a company’s future profits. And if a startup fails, as is often the case, the coins will be worthless.

So the tokens are more like a crowdfunding campaign than traditional venture-capital financing. No matter. Buyers are snapping them up. In the first 15 days of May alone companies have collectively raised $27.6 million this way, according to Smith & Crown, a digital currency and blockchain research firm. That compares with just $3.5 million for all of May 2016.

For companies, the coins are a new source of quick funding. One early offering was in November from a startup called Golem, which billed itself as “Airbnb for computers.” It essentially allows users to rent computing power, with the coin being necessary to get on the network. The Polish firm raised $8.6 million in half an hour.

For now, many coin buyers appear to be speculating the tokens will keep rising in value as they become more popular, allowing them to be sold for hefty gains. And the fervor around the coins has helped drive up the price of more established digital currencies like bitcoin and ethereum. Bitcoin surged over $1,800 last week and is up more than 80% this year.

Even some big investors are interested. Tim Draper, a well-known Silicon Valley venture capitalist and early bitcoin believer, plans to buy tokens in a coming coin offering for Tezos, a startup co-founded by a former Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs trader.

“What you’re doing is anticipating that the coin will become more important to people over time,” Mr. Draper said. Investors are essentially buying software, he added, not an asset that confers any ownership rights or claims on profits. But bottom-line returns aren’t the only — or even main — reason he’s getting involved. “It’s a way of thinking about how society might evolve,” he said.

So what could cause coins to gain value, other than speculators bidding up their price?

Source: Wall Street Journal

One possible way is if a coin-issuing company brings out a hot new technology product or software. New users would theoretically pay a premium to get access to that product, driving up the value of the tokens bought earlier. In that vein, it’s akin to joining a club a year or two before other people want in.

The knock on the coins is that the offerings are nothing more than the so-called greater-fool theory of markets playing out in the cryptocurrency world. “The investing public is mostly clueless,” said Francis Pouliot, who runs an information center in Montreal called the Bitcoin Embassy and has been critical of the coin-offering trend.

Even coins from startups with good prospects could be “bad investment decisions,” says Mr. Pouliot. For instance, a startup could eventually decide to cut the price of future tokens to boost the mainstream appeal of its product, hurting the value of outstanding coins.

Another concern: whether the coins will be regulated as investments. Companies issuing the coins consider them products since they can eventually be used to purchase goods or services.

Martin Koppelmann, a 31-year-old cryptocurrency enthusiast who co-founded Gnosis in June 2013, said his firm consulted with accountants on its offering but isn’t yet sure how regulators will react. “The worst thing that can happen is we have to pay a bunch of taxes and that would be fine,” he said. The company plans to use the proceeds to help build out its product.

The Securities and Exchange Commission declined to comment on regulation of the coins.

Others have been more cautious. Investment firm Blockchain Capital raised $10 million in early April as part of a third round of fundraising. Its coin offering was structured as a traditional securities investment, and the firm consulted lawyers to make sure it adhere to securities laws.

More recently, waves of speculative buying have sharply driven up the value of obscure coins in a short amount of time, itself a worry. Gnosis’ coins, for example, have tripled since they began trading on May 1, according to data from website CryptoCurrency Market Capitalizations.

Ondrej Pilny, an enthusiast who started a website to track coin offerings, has invested in several startups. He says he is attracted to their potential and the idea that they represent a new form of venture capital. Still, Mr. Pilny invests only in what he’s willing to lose “because cryptocurrencies and crypto assets are a very risky investment,” he said in an email.

Olaf Carlson-Wee recently launched a hedge fund focused on investing in new coins. He, too, says there are big risks. “Most of these will fail,” said Mr. Carlson-Wee. “Most of these are bad ideas from the beginning.”

For investors with a venture-capital mind-set, such failures can be acceptable if one investment in a group is a big winner.

Mr. Draper, the venture capitalist, acknowledged coins aren’t a typical bet for an investor like him, who has made big profits on investments in companies like Skype, Tesla and eBay . In some ways, “it’s like a nonprofit investment,” he said.

Despite that, Mr. Draper isn’t viewing his investment as charity. “I think we’re going to make a lot of money,” he said.

Source: Wall Street Journal